The Price of Half-Freedom:

Manuel de Gerrit de Reus;

Enslaved, Condemned, Pardoned & Freed, 1641-44

Now on view at:

Shirley Fiterman Art Center

81 Barclay St.

New York, NY 10007

September 15 - December 22

Open Wednesday to Friday 12-5 PM

Shirley Fiterman Art Center

81 Barclay St.

New York, NY 10007

September 15 - December 22

Open Wednesday to Friday 12-5 PM

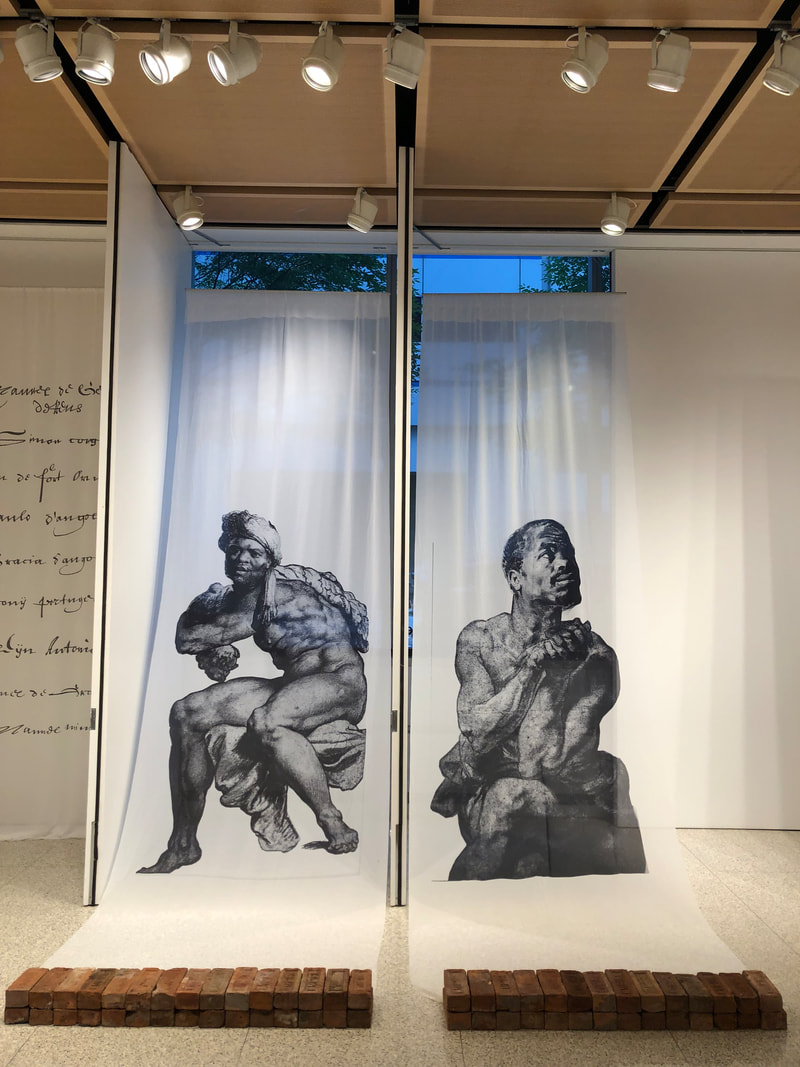

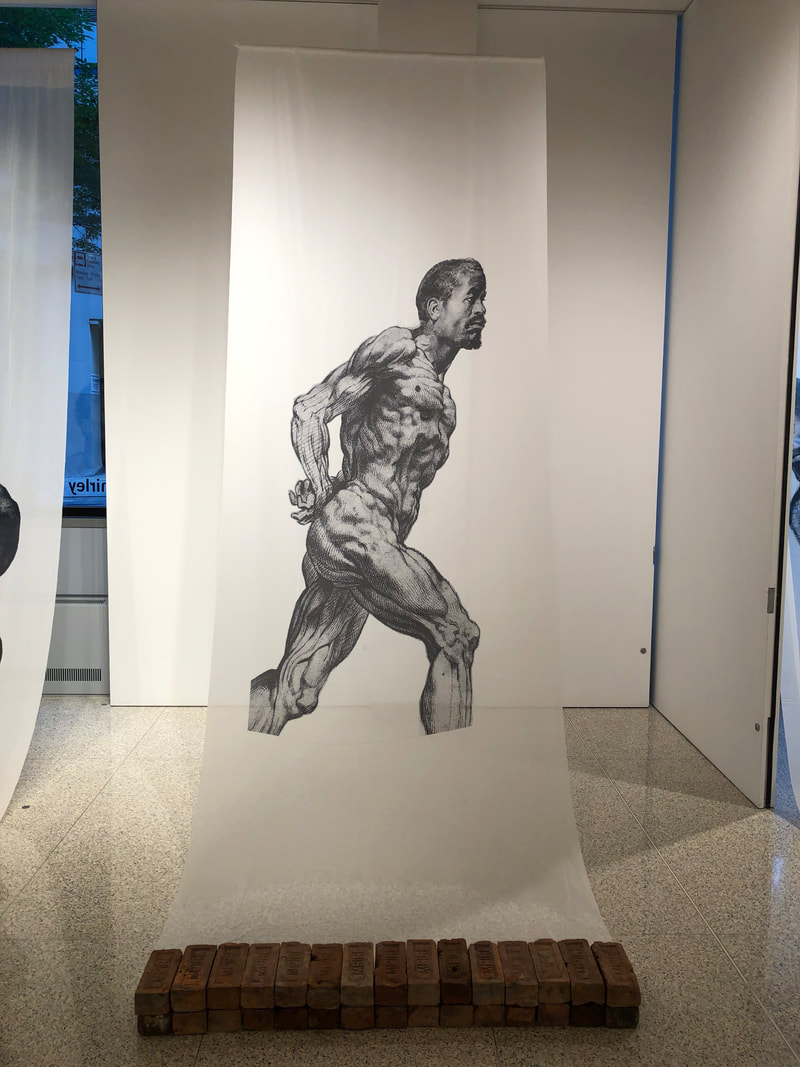

"The Price of Half-Freedom is comprised of an installation that includes video, historic documents, a sculptural brick work, and a sequence of large-scale prints on fabric appropriated from prints by Dutch artist Peter Paul Rubens and a number of other major European painters. The choice to appropriate Rubens stems from the artist’s unprecedented visibility and fame: both a diplomat for the Dutch Republic and a major figure in art history, Rubens is perfect symbol of the long standing interconnectedness between art and politics. In his practice as a multidisciplinary artist, - through projects such as this, Sovak examines the history and legacy of colonialism and seeks to reframe the historical narratives surrounding slavery—as well as art history—in the United States."

- Lisa Panzera, Director

- Lisa Panzera, Director

"The story of Manuel de Gerrit de Reus is the story of some of the first free Afro-Dutch citizens of New Amsterdam whose lives exemplified the kind of Black solidarity and Black resistance worthy of our memorialization."

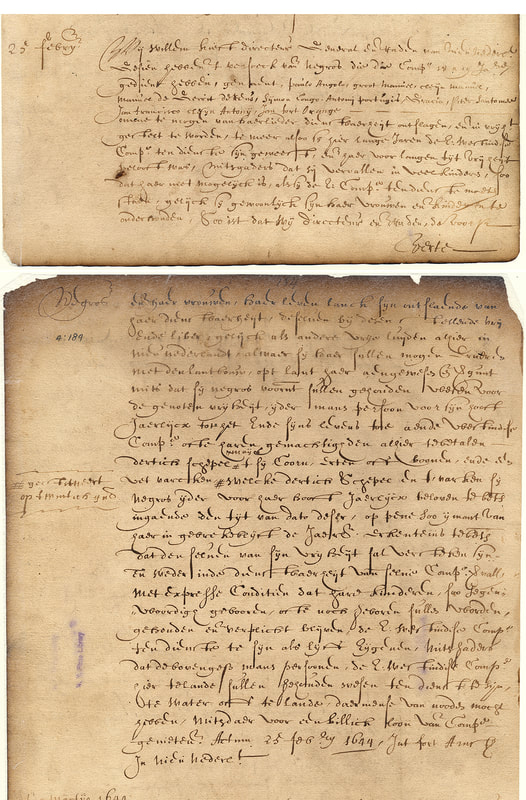

Dutch Colonial Council Minutes read by Marieken Cochius

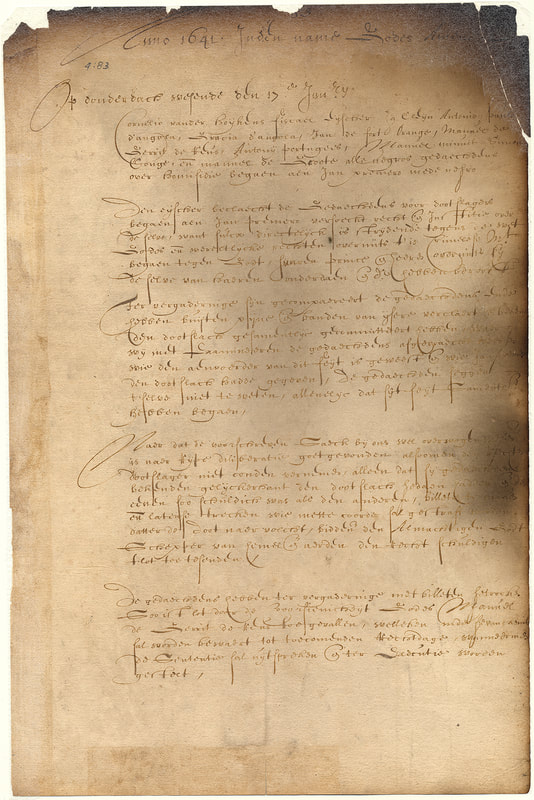

On January 24, 1641, Manuel de Gerrit de Reus stood at the gallows in Fort Amsterdam waiting to be executed. De Reus, whose name translates to “the Giant,” along with eight other Afro-Dutch enslaved men, had all confessed to the murder of Jan Premero, also a slave of the Dutch West India Company.

"All confessed to the crime and that each of them was as 'guilty as the other.'"

According to the Company’s Colonial Council Minutes, when the Council insisted on knowing “who was the leader” of this “crime committed against the highest majesty of God,” these nine men of African descent repeatedly insisted they did not know who gave Jan Premero the final death blow, and that each of them was as “guilty as the other.” These “Negroes” were ordered by the Council to draw lots to determine who would be punished for the crime, and de Reus was chosen “by the providence of God” to be “condemned to be executed with the rope until death ensue.”

"when his body fell both nooses around his neck broke and he miraculously survived."

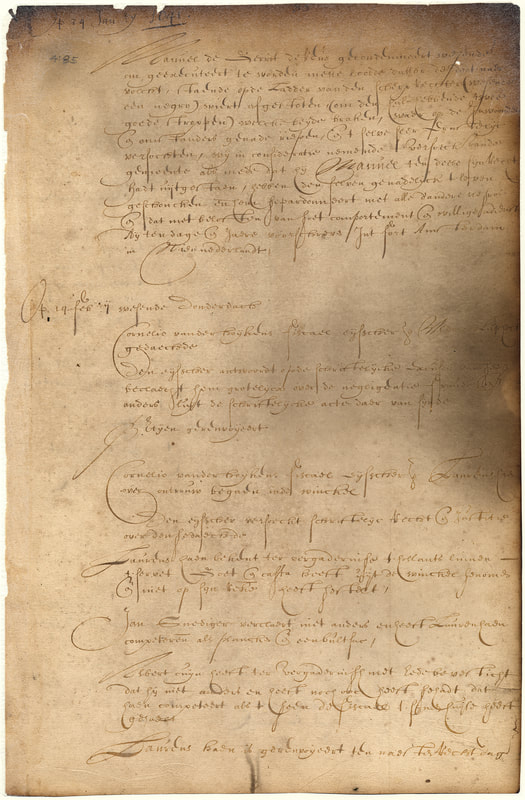

In Spaces of Enslavement: A History of Slavery and Resistance in Dutch New York, author Andrea Mosterman notes that the settlers of New Amsterdam gathered on that cold January day to witness de Reus’s hanging, but when his body fell both nooses around his neck broke and he miraculously survived. The spectators pleaded for clemency, arguing that this turn of events was evidence of divine intervention. De Reus and the eight others were granted pardons and later, after petitioning the Council, were granted half-freedom. The conditions for this freedom were that, in exchange, these men and their wives had to make a yearly payment to the Dutch West India Company, and their children (even those yet to be born) would remain in the Company’s servitude.

"Did he know that when he was pushed off the ladder he would not die?"

When de Reus was standing on the ladder about to be put to death by the executioner who was also a “Negro”, did he know that a miracle was about to occur? Did he know that when he was pushed off the ladder he would not die? Did he know that he and the others would be exonerated and later conditionally freed?

The historical record suggests that the God against whom de Reus had been accused of committing a crime was the same God who chose de Reus to be punished, and then wonderously, at the last minute, chose to spare his life. I would like to speculate that in reality a miracle of a much more human nature occurred that day: the nine Black men who confessed to the murder of Jan Premero were willing to be jointly accused of a crime that carried a death sentence because they knew that they stood a better chance of survival by standing together, guilty, rather than individually, in innocence. By leveraging their collective value against what the Dutch West India Company called “justice,” these nine Black men secured for themselves, and others, a conditional form of freedom two hundred years before the Emancipation Proclamation.

We will never know who killed Jan Premero, but his death launched an historic battle of Justice vs. Righteousness, Mercy vs. Profit. I believe the story of Manuel de Gerrit de Reus exemplifies the kind of Black solidarity and Black resistance worthy of our memorialization.

The historical record suggests that the God against whom de Reus had been accused of committing a crime was the same God who chose de Reus to be punished, and then wonderously, at the last minute, chose to spare his life. I would like to speculate that in reality a miracle of a much more human nature occurred that day: the nine Black men who confessed to the murder of Jan Premero were willing to be jointly accused of a crime that carried a death sentence because they knew that they stood a better chance of survival by standing together, guilty, rather than individually, in innocence. By leveraging their collective value against what the Dutch West India Company called “justice,” these nine Black men secured for themselves, and others, a conditional form of freedom two hundred years before the Emancipation Proclamation.

We will never know who killed Jan Premero, but his death launched an historic battle of Justice vs. Righteousness, Mercy vs. Profit. I believe the story of Manuel de Gerrit de Reus exemplifies the kind of Black solidarity and Black resistance worthy of our memorialization.